A window on the real story of the Irish

The passing of a great bookseller reminds Joseph O’Connor that our story is not that of Nama and ineptitude

Sunday October 17 2010

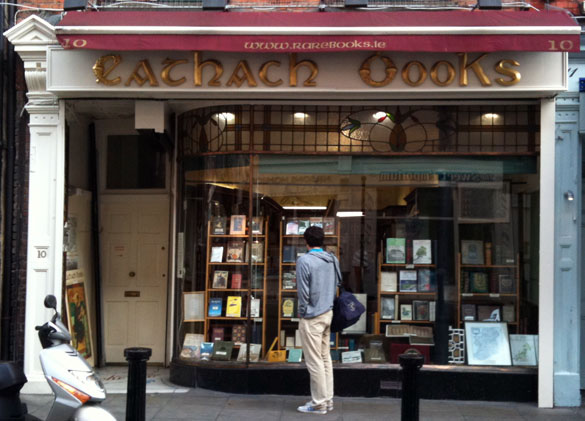

Some time when you’re in Dublin and you’ve half an hour on your hands, you might take a walk down Duke Street and pause before the windows of the unflashy old bookshop you’ll find near the corner of Dawson Street. The name of the store is Cathach Rare Books (now Ulysses Rare Books), and it’s named after an event in ancient Irish history when two saints had a tussle over an important question: who owns the rights to a story?

The shop specialises in beautiful old books and rare editions, and so, as you stand before that window among passers-by and buskers, you see part of our own story too. Yeats, Heaney, Wilde, Friel, Beckett, Kavanagh, Mary Lavin, Edna O’Brien, the plain blue-green wrapping in which James Joyce’s Ulysses first sidled into the world.

Once, as a kid, I saw a documentary by the sea-explorer Jacques Cousteau, in which he said that when he looked through the glass-bottomed floor of his boat he saw a world “of strange beauty and angels”. When you look through the window of that unassuming shop on Duke Street, the ghostly angels sometimes seem to look back at you. The remarkable, beautiful, treasurable things Irish people have achieved in language.

To leave the street and enter that shop is to step briefly out of the worries of our time and into the realms of gold. There is the particular and immediate restfulness of places where old books are gathered, that sense of quiet dignities and accumulated wisdom. There is that reminder of the consolation of reading in a difficult time, and there is the beauty of the books themselves.

A sad thing, perhaps unnoticed because of tough economic news, is that we are living through the era of the death of the book, the most wonderful piece of technology ever invented by our species. My grandchildren will only read onscreen — a great thing in its way, but they will never know the joy of opening a hardback, of finding an old note or a forgotten photograph in the pages of a novel. In that little shop on Duke Street, the visitor is reminded of what happens when a tide goes out.

For many years, that shop was run and cared for by a man named Enda Cunningham, who would sit at his book-laden desk just inside the door, like the sentry of a secret garden. He was a quiet man, a Northerner, with a modest, assessing face, a scrupulous scholar who took his work seriously. I never knew him well, but it always occurred to me that here was a man who, in his own unassuming way, embodied what was best in us. Respect for learning. Reverence for a culture. Knowing what is important in the end.

If you spoke to him about a book, he knew everything about it. The catalogues he produced were works of extraordinary scholarship and beauty. And I noticed, once or twice, when I was browsing in his shop, that he treated people with a courtesy some would consider old-fashioned now. If someone wanted a first edition of Ulysses, Mr Cunningham would probably have one, and since only 1,000 of those were ever printed, it wouldn’t come cheap. But he once put many hours into finding me a book I wanted. Its cost was €25.

Cathach: an ancient argument about who owns a story. But the question is one we face just as sharply now. How did we get here? Where are we going? What is Ireland for? But to remember the great things achieved by Irish people in culture is to be reminded that our story is not over.

We are not condemned to be ruled by mullahs and mediocrities. We are better than Nama and scandal and embarrassment. The shame brought on us by our leaders, with their ineptitudes and evasions, their cavorting in cupboards and stupid parliamentary games, is not how we should define ourselves. The better part of us is still alive and can be seen every day: in the service given by carers who look after the vulnerable; in the affinities we still feel, even when we are frightened; in the window of Enda Cunningham’s shop.

That gentle, studious man passed away last month, and he will be missed by people who loved books, as he loved them himself. His shop is still there, capably run by his family, and the values he lived by are still the ones we respect most.

Often, when I browsed in Mr Cunningham’s shop, I thought of a paragraph from the great poet John Donne I think he would have liked; and I write it out for him now, in affectionate remembrance, and for all of us who need reminding that we write our own story, no matter how the powerful would divide us.

“All mankind is of one author and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated. God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God’s hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.”

Broadcast on ‘Drive Time’

RTE Wednesday 13th October 2010